Quest to See the Aurora Borealis, Part 2

"He knew, by the streamers that shot so bright,

That spirits were riding the northern light."

--- Sir Walter Scott, 1802

Fifty-six miles outside Fairbanks, Alaska, a snow-packed, two-lane road dead-ends at the Chena Hot Springs Resort. Eighty comfortable rooms await visitors from around the world who swim in the natural hot springs and ride the dogsleds, snowmobiles and horse-drawn sleigh.

Fifty-six miles outside Fairbanks, Alaska, a snow-packed, two-lane road dead-ends at the Chena Hot Springs Resort. Eighty comfortable rooms await visitors from around the world who swim in the natural hot springs and ride the dogsleds, snowmobiles and horse-drawn sleigh.

There's an even bigger attraction at this resort in the long, cold winter, due to Chena's proximity to the Arctic Circle and great distance from the light pollution of any city or town. The property has built a reputation as a good place to search for the northern lights, which the natives of this land once believed were the dancing souls of the dead.

Our group of six arrived from Houston at 1 am local time (4 am Houston time), to find the soft lights of the sprawling compound filled with falling snow. Following a quick check-in, we added another layer of clothes and made our way to a dark clearing by the lodge's private landing strip.

For an hour, we stood on the snow, staring into the northern sky, adjusting our hats and coats against the -15 degree F cold, but on this day, there was nothing there to see. We climbed into bed with frozen feet, for a few hours of sleep, and were up again before the sun rose, at 10 am.

In the four hours before sunset, at 2 pm, we drove snowmobiles through the surrounding countryside, took a dogsled ride, and hiked the snowy trails nearby. Sometime after sunset, we had lunch, and a few hours later, dinner.

If this sounds a bit disorienting, let me assure you that it was. But all day our anticipation grew for the evening's main event, an excursion to the top of a nearby ridge for a better vantage point from which to search for the Aurora Borealis.

By 9:30 pm, we were on our way. Our large-tracked snow coach groaned and shuddered up the hillside, headlights cutting through the blackness and illuminating thin spruce trees weighed down by snow. At times the slope was so steep we slowed to a walking pace, the engine straining under the load.

In 30 minutes, we climbed 1,500 feet to the summit for what could have been a panoramic view of the Alaskan sky, far from any light pollution. But the summit was shrouded in clouds and bitterly cold, -20 degrees F and falling. So cold we could not warm our hands after removing our gloves to fumble with our cameras, and so dark we could not see the falling snow, only feel it on our faces.

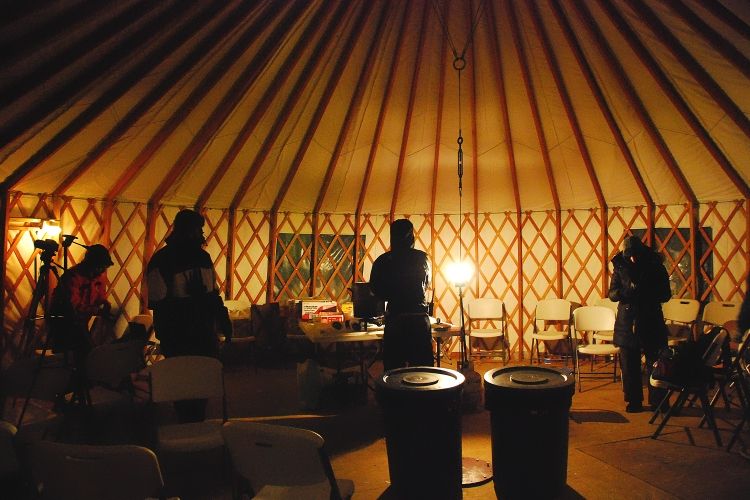

Those with tripods (an absolute necessity for photographing northern lights) fanned out across the fresh snow to look for a level spot to set up, while the others quickly found the yurt, a circular structure covered in ice and snow that offered the only protection from the elements.

Once our group's tripods had been positioned, we too retreated to the yurt, a half-lit tent with gas heaters that eventually warmed the air above freezing, and much later, to the point that we could no longer see each breath.

Every 20 minutes or so, someone from our group went out to check the cameras and scan the sky for any break in the clouds, but that was not to be. After four hours, we retrieved our equipment for the return trip and found our cameras and tripods covered in ice crystals.

We climbed into the snow coach for a much faster race down the mountain and fell into bed after 2 am. The day ended as the first had, without a glimpse of the northern lights.

On our third and final day in Alaska, New Year's Eve, we awoke to find the gray sky filled with large flakes of snow. We learned that the lodge's temperamental Internet connection was up and rushed off all-is-well emails to friends and family.

We toured the ice museum, filled with delicately carved ice sculptures, a full-size ice bar and ice bedrooms, and lit by ice chandeliers. We ate more meals in the dark, though by now "lunch" and "dinner" had lost their meaning.

At 10 pm, we went outside for an exhilarating fireworks display directly over our heads. The flashes illuminated the falling snow and the bigger bursts lit the hillside to the north.

As the display continued, the clouds began to clear and in minutes, they were gone. As the last flash of pyrotechnics faded from our retinas, a canopy of brilliant stars unfolded across the black Alaskan sky.

The rest of the lodge's guests filed back to the bar or to their rooms, but our group remained behind, in the dark, peering into the Milky Way.

Approaching midnight, with a 4 am wake-up call looming for our shuttle back to the Fairbanks airport, it was now or never for us -- our last chance to see what we had come so far to see. The sky was clear for the first time in three days, but would the solar wind accommodate us?

Suddenly, miraculously, the hillside to the north became more prominent, silhouetted, as if a town had sprouted on the far side to backlight the summit. Within minutes, the light moved from behind the hills to above them, strengthened in intensity and began to spread to the east and west, first in one long arc and then another. We laughed and giggled and high-fived like children as the green aurora unfolded before us.

The solar wind bathes all the planets in our solar system, and auroras have been detected on Saturn, Jupiter, Neptune and others. Every planet with an atmosphere, including the large moons of the outer planets, experiences auroras under the right conditions.

Maybe that's why I could not help feeling part of something bigger as I stared up at our extraterrestrial visitor, a celestial light show that is always happening somewhere, whether or not we can see it.

There have been more brilliant auroras I am sure, with more colors and more movement, filling the entire sky. But our small band of pilgrims could not have asked for more.

In this wondrous age, there is always something new to find for those who go looking. I wish you the same good fortune on all your quests this year. And may the wind be with you.

Sincerely,

Alan Fox

Executive Chairman

Vacations To Go

Related newsletter:

Quest to See the Aurora Borealis, Part 1